For most of human history, we spent our days hunting and gathering food, wherever we could find them. If a particular area was lacking in nutrient rich supplies, or if it was being made use of by another band whom we didn’t want to war with, then we would simply wander somewhere else and make hay wherever the nutritional sun shone.

About 10,000 years ago, our ancestors stumbled across the seemingly genius idea of domesticating animals and cultivating easy to grow foodstuffs so that we could experience plentiful supplies of essential foodstuffs without having to wander the savannah.

Climatic conditions at the time were ripe for this sort of development, and the Middle East began the trend by domesticating goats and cultivating wheat. Peas and lentils followed in the Levant, and later olives, horses and grapevines added a little variety to our newly sedentary lives. Meanwhile in Central America there were simultaneous movements towards the cultivation of maize, beans, potatoes and llamas and in the Far East, it was rice, millet and pigs.

The immediate effects of their work were greater overall supplies of food. However, the work was hard, and so these newly formed communities took advantage of the surplus food supplies by having more children who could share the load and work the farms.

Who could blame them for wanting the help? Our bodies were simply not yet adapted to this type of living. We were used to wandering from place to place, climbing trees and chasing animals, not clearing the land, sewing seed and harvesting the produce. Our skeletal integrity was soon suffering due to the wear and tear of this tough farming life and so reproduction became the way to seemingly get ahead.

Indeed, the sorts of crops that lent themselves to domestication required constant attention and protection from pests and climatic conditions, so the extra hands would hopefully make light work of our attempt to conquer nature.

However it wasn’t just our skeletal structures that suffered. Our digestion did too. Our biology had adapted to nutritional variety, not this slimmed down agricultural diet we were subsisting from. And the substitution of grains for the four years of mothers milk we had learned to grow in in pre-agricultural times, created a weakening of our immune systems. Our communities soon became rife with disease when previously this has been much less of a feature.

Our psychology was also affected greatly. In theory we were safer, for having fields of gold left us with a golden supply of foodstuffs that could be stored when times were tough. But the lack of variety in our cultivation meant we were more exposed to systemic risks to the food supplies if a particular pest came along. We could build granaries to hoard our supplies, but then these became tempting to others who may not have had our foresight and then we had to build walls around our communities to protect them from fiends.

Such complexities caused us to go from living in the moment, living off whatever nature’s bounty supplied us, to suddenly having to think about climate, pests, neighbouring communities etc etc. We had to plan for the future in ways that we never dreamed of previously. Iit caused us to live in our heads, constantly thinking about what was going on in the fields, rather than simply enjoying being part of a tribe that spent much of its time socialising and having fun.

It also meant we were tied to the land now. We became possession oriented. Having grown our communities to till the land, and having slowly lost the art of foraging, we became dependent on the farms that we created to provide us with our basic calorific needs. We now had something to lose.

We began to feel less safe as a result of being less agile. If strife came, in the form of hungry villagers from another community, we would now have to fight to the death to save our families and friends, rather than simply flow with the fluctuations of life on the savannah. When this is your prevailing experience, it changes your neurological and neurochemical profile to the status of background fear mode. At least when trouble came previously, we had the option of running. Now the only option we had was to fight.

With each passing generation, we came up with ever more innovations to improve our lot. But each passing innovation triggered a cascade of unintended consequences we had no idea about. Freedom from the grind was always on the horizon, one harvest away from being realised. And yet, with each passing year, and each passing generation, the increasing complexities and energy requirements of our increasingly complex societies required us to work harder and harder, just to stand still.

As the human population expanded, we needed bureaucracies and lawmakers to keep everything in order. We were no longer small communities who could police themselves. With large numbers of people physically stressed by their work and in psychological fear mode, the population needed ever more policing. With such bureaucracies came hierarchies who needed feeding, and these self-interested parties, who were no longer connected to nature, found themselves stereotypically attempting to grow fat off the land through taxes and other such ‘protection rackets.’

Instead of taming the crops for the betterment of our lives, we found ourselves tamed by the very crops who we had become dependent on.

Although this is an ancient story, it reminds me of the life we now find ourselves living. With each passing year there is ever more technology abounding, all holding the promise of making our lives easier. Yet, with each passing development, we seem to become ever more dependent on the very innovations that are supposedly making our lives easier. The hamster wheel of life is getting faster and faster but are we any happier? It seems not. We are simply more busy.

We sell ourselves the ideal that if we work hard for just a few more years, then we can take our foot off the gas and start living the dream but it rarely seems to materialise. Instead we find ourselves chained to the very way of life we have become accustomed to. When we earn more money, we start dining out, we start taking taxis instead of public transport and we take more expensive holidays to recompense us for the strains of our everyday existence. All of this is like lifestyle crack that is very difficult to wean yourself off. Before you know it, your ‘comfortable’ lifestyle has graduated into a baseline expectation of how life should be. There is no going back, even if the more simple life felt like a relative utopia compared to the grind of life in the fast lane. We are trapped.

Advertisers instinctively understand this dynamic and make great hay from selling us the possibility of a better life. But the promises they make are always of an improved external circumstance.

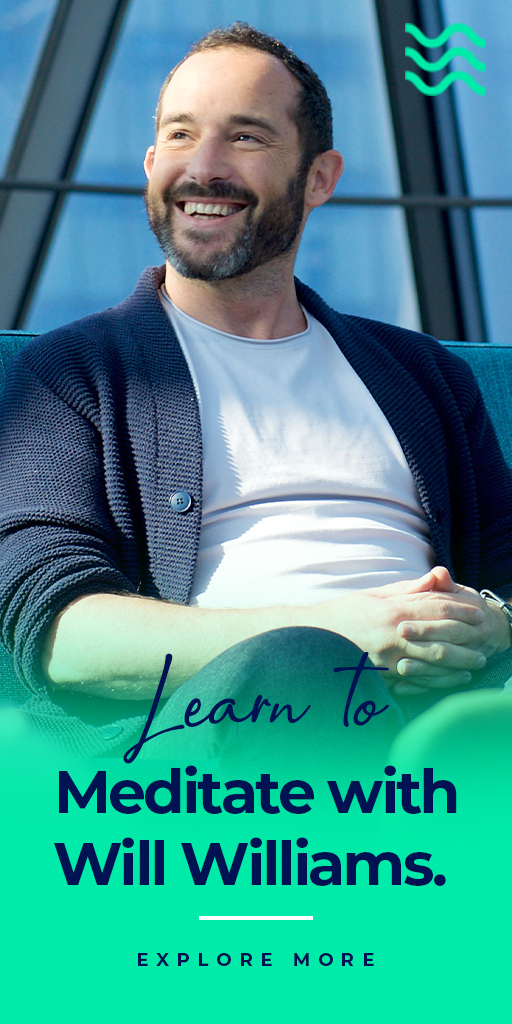

What we humans really crave is an improved internal circumstance and that’s where regular meditation really comes into its own. It is an internally derived energy source. It gives us the power to tune into to what really matters to us. It helps us step out of fear mode and into something that fosters greater personal and community relations. Unlike the agricultural and technological revolutions, it improves our digestion and our immune function, rather than make it worse. It makes us more agile by boosting our adaptive capabilities, rather than less. It improves our skeletal structure by reducing stress and improving the calcium uptake into our bones. It ultimately helps us realise that our mind, body and nervous system are our home. When they are in good condition, we can leave the wheat field or the employment mothership and take our innate capabilities wherever we like. We become a vehicle for fulfilment rather than a seeker of it.

We cannot turn back the clock, it is water under the bridge. We can only orient ourselves towards the ever moving present. We cannot control our external world but we can master ourselves and master life so that it works for us rather than us working for it. That ladies and gentleman, is the closest we can ever come to being truly free.

Meditation improves the past. It massively improves the present. And it most assuredly improves the future.

The Benefits of Beeja Meditation

- Reduce stress and anxiety

- Greater clarity and calm

- Increase focus

- Enhance relationships

- Sleep better

- Feel energised