In light of our organic-driven Ayurvedic cooking workshop, Organic September and our fruitful collaboration with healthy food specialists Hemsley + Hemsley, today’s blog is about the history of farmed foods and the inexorable rise of one of our favourite industries: organic produce.

Food has been the defining factor in humanity\’s development and proliferation, and farming has been at its heart. It was the cultivation of crops that allowed people to give up their nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles for a more stable existence, and developments in farming techniques which catered to a growing population as crises of human health were averted. But as the number of farmers has plummeted and the population continues to rise, some are worried that the quantity of produce is affecting its quality. As conventional farming chases bigger produce and bigger crops, the organic industry has emerged touting a radical principle: it’s not the size of the vegetable that counts, but what you do with it.

Beginning between the World Wars and taking hold in the swinging 60s, the Green Revolution had the noble goal of preventing starvation in the face of a global population crisis. This scientific approach to increasing crop yield saw major test cases in Mexico, India and the Philippines. Careful cultivation and improvements to farming techniques improved Mexico’s self-sufficiency; in India and the Philippines, specially bred strains of rice and the implementation of hydroponics and pesticides increased yield tenfold, turning both countries into major rice exporters. These principles and the development of genetically modified produce have continued unabated ever since, with continuing efforts to apply these principles to solve Africa’s food shortages.

As with so many good natured changes to our environment, however, there have been unintended repercussions. The use of pesticide DDT turned out to be a deadly mistake, with the toxin washing off of fields and into the food chain, driving some birds and fish close to extinction. Now a new threat is manifesting itself in the quality of food being grown. Numerous scientific studies indicate that modern day vegetables from conventional farming have a significantly diminished amount of vitamins and nutrients compared to pre-Revolution produce. At the same time, inadequate nutrition has joined malnourishment as one of the World Health Organisation’s primary concerns, with the Center for Disease Control estimating that 2bn people have at least one micronutrient deficiency. With business interests stymying change in the farming industry, organic food offers a return to more nutritious food, and with it an impetus for wider change.

The risks of pesticides and genetic modification continue to be investigated, even as comically evil firms like Monsanto concoct plans in volcano lairs for zombified corn. But the most contentious changes brought by the Green Revolution are those which have already saved so many people: improvements in efficiency. The use of irrigation techniques such as hydroponics, synthetic fertilisers and genetic modification to produce high yield plants appears to relate inversely to their nutritional value. Sweeter varieties of sweetcorn and carrots for instance, often denoted by a paler colour, have been preferentially bred to the detriment of their micronutrient content.

Fertiliser is often used with the aim of growing large plants rather than supplementing other nutrients that are taken out of the soil, while crops are not rotated and land is not left to recover for long enough before the next one is planted. And while the impact of pesticides on the soil biome is unproven, the speed at which produce is often grown and harvested means that plants don’t have enough time to grow roots deep enough to make the most of it. Fruits and vegetables are often picked before they are ripe so that they have a longer shelf life for international journeys, cutting out even more time when they might have been absorbing more from the soil. And all the time they spend out of the soil, their nutritional value is diminishing.

The potential benefit of organic produce is that it avoids all of these practices. In compliance with standards set by the European Union and other significant bodies, organic farming precludes the use of genetic modification, limits the use of pesticides and fertilisers, and prioritises the use of crop rotation and composting to improve soil quality, and thereby the quality of the produce. The largest ever peer review on the quality of organic and non-organic food in 2014 concluded that organic produce contains a significantly higher level of antioxidants, comparable to eating 1-2 extra portions of fruit and veg a day. Most organic food is also sourced domestically and as such has a smaller carbon footprint, while the process of tilling soil also helps to release less greenhouse gas. That means fewer Spanish strawberries coming over here and stealing our shelf space, but it’s also a huge boon in the fight against climate change, where rising temperatures and drought have the potential to damage crops even further.

There are skeptics, however. While many people swear by the fresh, sweeter taste of organic produce, this has supposedly been debunked by several studies, with participants indicating that a regular foodstuff mislabelled as organic tasted better than a similar non-organic one (there was a fatal error in this test, however: it didn’t use my home grown tomatoes, which are scientifically proven to be delicious). And while the evidence on soil quality and levels of antioxidants in organic produce holds up, a few scientists questioned whether this was a major revelation. While antioxidants are certainly good for you, they aren’t considered to be among the key micronutrients needed by humans, where studies indicate there is less of a difference between organic and non-organic food.

The falling levels of nutrients in fruit and vegetables over time is indisputable, but this could owe itself to all kinds of other changes in the intervening years, from pollution to climate change and even lingering damage from old pesticides. There are arguments that genetic modification has led to fast-growing veg that doesn’t absorb or produce as many nutrients, but much of this could also be down to hundreds of years of selectively breeding popular varieties of produce. This isn’t something organic farming necessarily stops: your organic corn on the cob might have been grown in a more sustainable manner, but it’s unlikely to be black or purple, as the more nutrient-rich original strains of the plant were.

In spite of these queries, there is no reason not to eat organic if you can afford to do so. Prices are falling too, driven by competition between supermarkets and retailers such as Whole Foods. While the breadth of the benefits is somewhat disputed, there are only benefits, and the impact ranges beyond the effect on your body. Organic farming has an undeniably positive impact on the local economy and the environment, with no pesticides harming wildlife or the environment and fewer flights polluting the atmosphere. In the race to feed the world, saving it is just as important, and organic farming will open up new avenues for exploring the best way to achieve both goals.

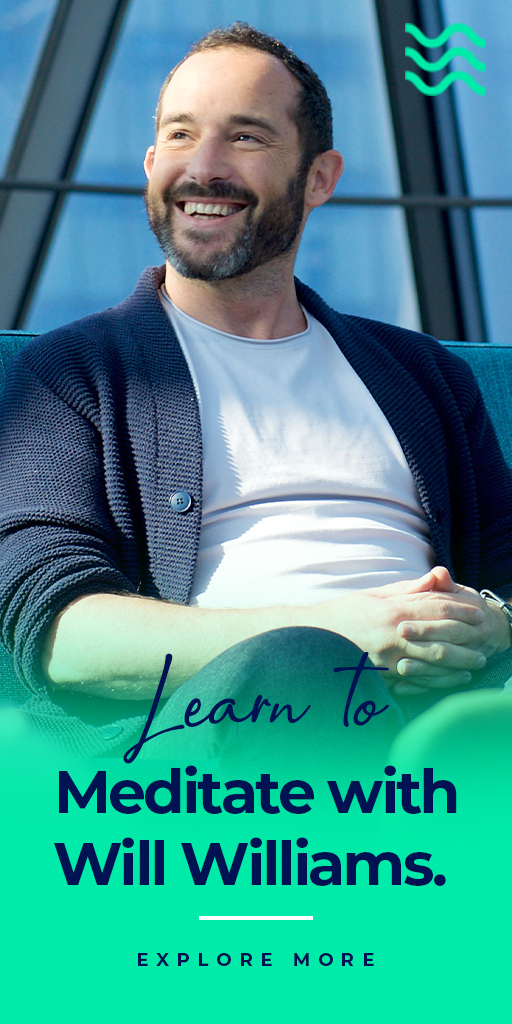

The Benefits of Beeja Meditation

- Reduce stress and anxiety

- Greater clarity and calm

- Increase focus

- Enhance relationships

- Sleep better

- Feel energised